Elective recovery gets underway

The clearance of England’s elective waiting lists accelerated again in September, with the reported referral-to-treatment (RTT) waiting list shrinking by 195,000 patient pathways year-on-year, up from 103,000 to the end of August. About 50,000 of the reported reduction was caused by counting changes early in 2024 (when community services and a large mental health trust dropped out of the data) but the lion’s share of the improvement is real, and welcome.

This acceleration needs to continue if the statutory 18 week standard is to be restored by the end of this Parliament, as the Labour government pledged in their election manifesto. In round numbers, the waiting list needs to shrink by about four million patient pathways by March 2029, which is four whole financial years away, so the year-on-year reduction needs to reach roughly one million per year. That pace is the magnitude of the rapid backlog clearances of the New Labour government back in the noughties, but in those days the NHS budget was doubling in real terms which is very much not the position under today’s financial constraints.

The challenge in the current planning round will be to ensure that 2025-26 contributes a full year’s worth of elective recovery, despite the pressures.

In the following discussion, all figures come from NHS England. You can look up your trust and its prospects for achieving the waiting time targets here.

The numbers

During the covid period, year-on-year growth in the English RTT waiting list peaked in June 2021 at 1.6 million patient pathways a year. Things started to turn around in early 2022, meaning that they were getting worse less and less rapidly. By the summer of this year, that deterioration had tipped into recovery. For as long as it remains this side of zero, waiting lists and waiting times in England will be getting better over time rather than worse.

For the first time since the unusual months of the covid shutdowns, the English waiting list is shrinking rather than growing. In the next chart, the red rectangle shows where the list size needs to get to, before the 18 week standard can be restored. Exactly where in the rectangle depends on the shape of the national waiting list (which is plotted in another chart below), and the shape depends on how accurately resources are deployed over the next few planning rounds.

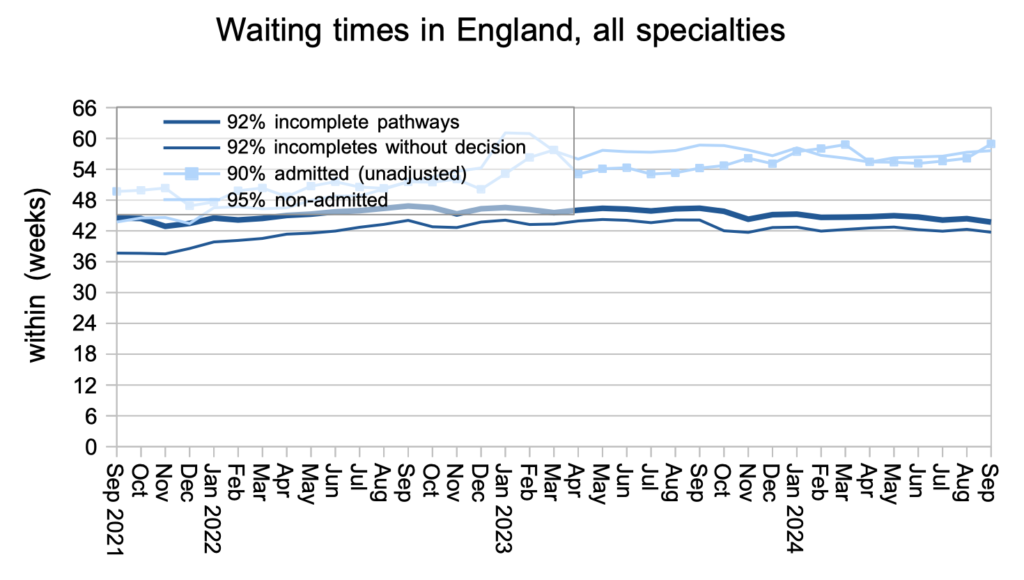

Slowly, the waiting list reductions are beginning to show up in waiting time reductions. This is what matters most to patients, especially the estimated 27,778 who are waiting a long time for a diagnosis that will unexpectedly turn out to be cancer – the typical wait from referral to diagnosis and decision was 41.7 weeks at the end of September.

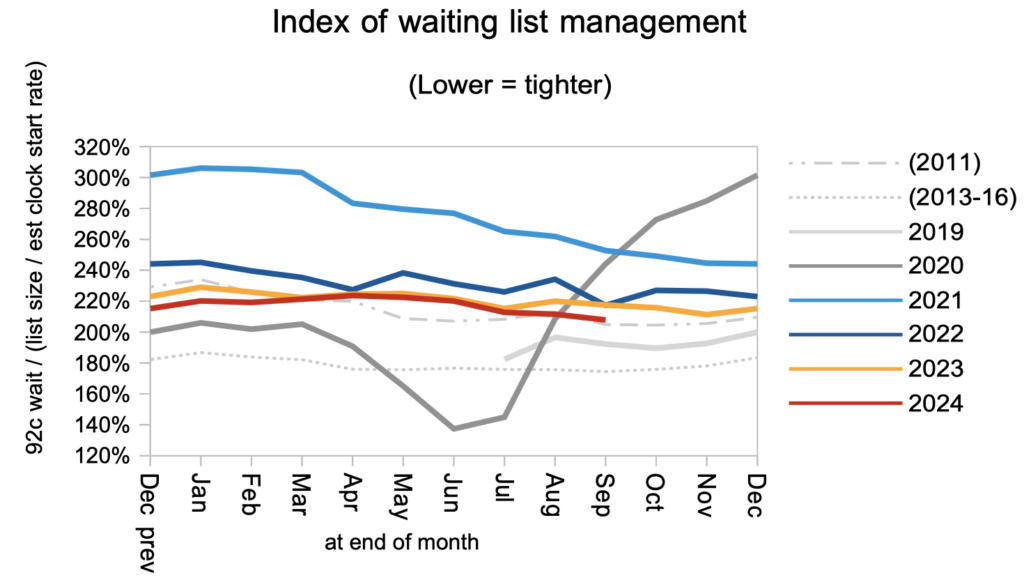

The shape of the waiting list at national level is driven by variations in waiting times pressures across the country, and the order in which patients are booked in locally. The 18 week standard will be restored more quickly if the shape can be restored to the 2013-16 levels shows in the chart. Currently the shape is worse than in 2011, just before the improvement which followed the introduction of the current statutory target.

Looking at waiting times by trust and by specialty, we can see that waits improved slightly but noticeably in September across much of the distribution. The restoration of 18 week waits will require the whole curve to approach the April 2013 level.

Plastic surgery had the longest England-wide waiting times again at the end of September, with the larger specialties of ENT and oral surgery close behind.

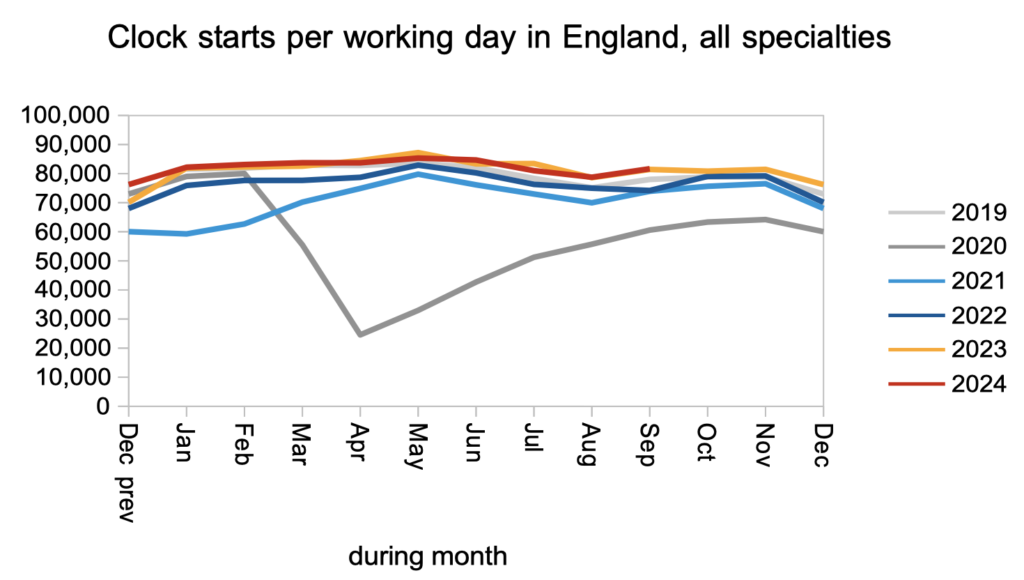

Waiting lists shrink when patients leave the list faster than they join it. The rate that patients joined the RTT waiting list and started new waiting time ‘clocks’ has remained close to last year’s levels all year.

Patients were removed from the waiting list for reasons other than admission (mainly as discharges from outpatients, or administrative removals) at faster than 2023 rates in September. A large majority of waiting list patients are waiting for outpatients and diagnostics, so this is where the sheer numbers are. It is also where unsuspected cancers and other urgent conditions are waiting a long time to be diagnosed, which is a significant clinical risk on the waiting list. For both reasons, increases in non-admitted clock stops are especially welcome.

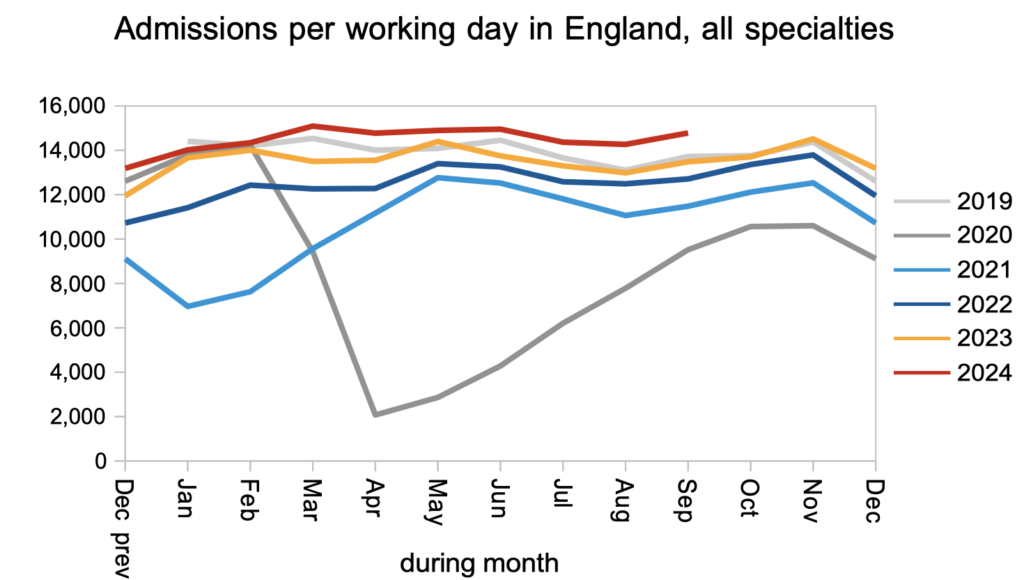

Patients continue to be admitted from the waiting list at higher rates than in recent years. Although the numbers are smaller on this part of the waiting list, the costs and capacity requirements are much higher. In a resource constrained environment there is always a temptation to let this activity slip, but then it can slip very quickly as outpatient backlogs are cleared and patients convert to waiting for admission. So it is important, when planning, to keep a lid on admitted patient waiting times, even if the main focus is (rightly) on reducing waits for outpatients and diagnostics.

Referral-to-treatment data up to the end of October is due out at 9:30am on Thursday 12th December.