Big improvement in waiting lists and times

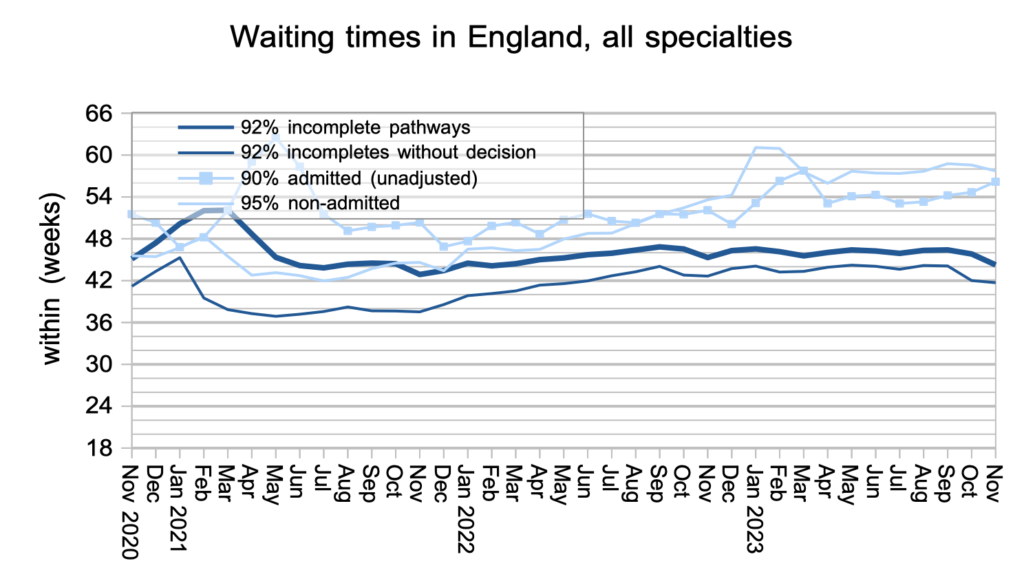

The English referral-to-treatment (RTT) waiting list shrank by 96,000 patient pathways in November, and waiting times also fell by 1.6 weeks to 44.3 weeks RTT. These are big improvements and a welcome step in the right direction.

NHS England simultaneously published supplementary statistics from the Waiting List Minimum Dataset (WLMDS) showing that the improvement cannot be explained by use of the recent ‘unlawful’ guidance, which reduces patient choice by allowing hospitals to remove patients from the waiting list if they twice decline the NHS’s choice about where and when they should receive healthcare. Around 400 patients per month are removed in this way, which is far too small to explain the reduction in list size.

The picture was more mixed for the very longest-waiting patients. Targets to eliminate over-104 week and over-78 week waiters have already been missed, and the number of breaches increased in both cases. The next targets are to eliminate 65-week waiters by the end of March this year, and 52-week waiters by March next year, and although the number of breaches reduced in both cases there is no realistic prospect of the 65-week target being achieved.

In the following discussion, all figures come from NHS England. The figures presented here do not yet take into account the revisions of historical data released at the same time. You can look up your trust and its prospects for achieving the current waiting time targets here.

The numbers

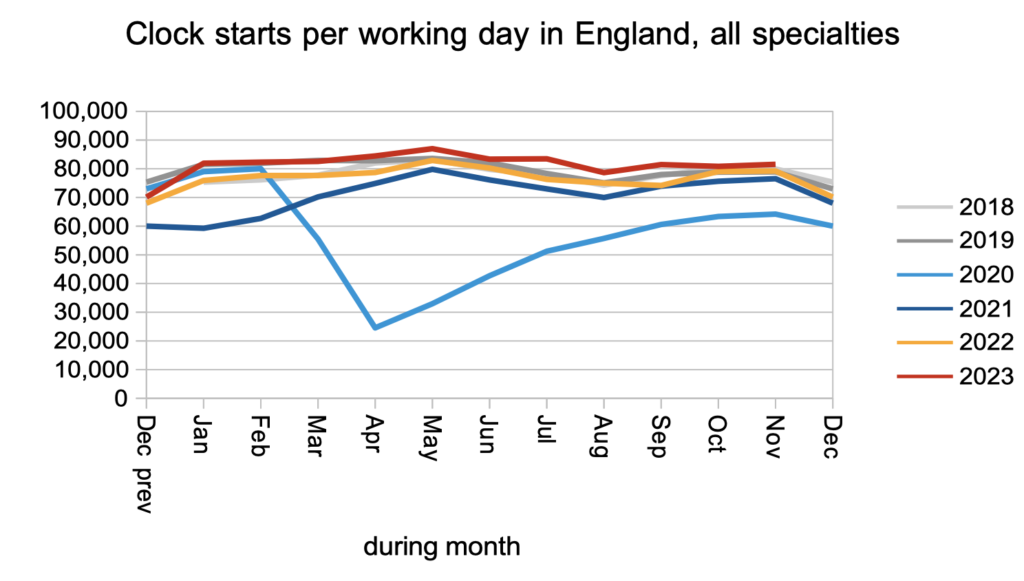

Demand for elective care remained at pre-pandemic levels, as measured by the numbers of patients starting new waiting time ‘clocks’.

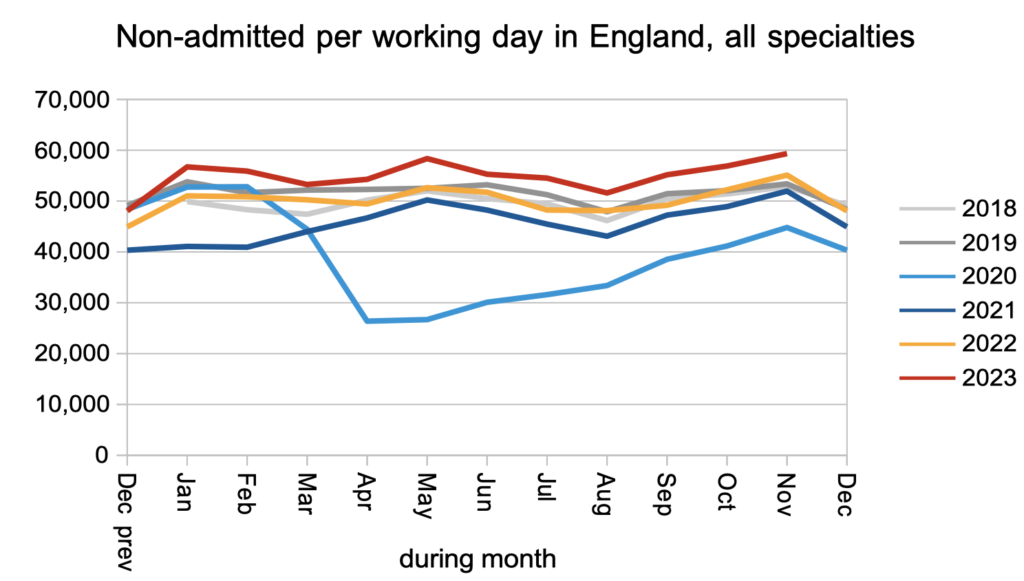

The number of patients leaving the waiting list following an outpatient appointment, or removed administratively, remained significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels. This is important because most patients on the waiting list are at the outpatient stage, and most of them are undiagnosed, so getting more patients to diagnosis reduces the amount of unknown clinical risk on the waiting list.

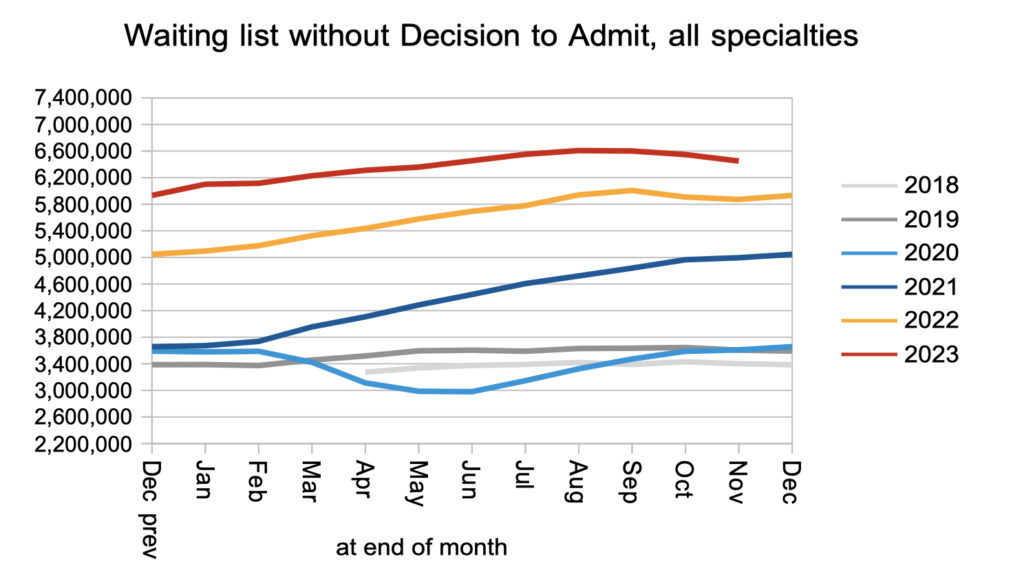

The upshot was a welcome reduction in the numbers of patients waiting list for diagnosis and decision to admit.

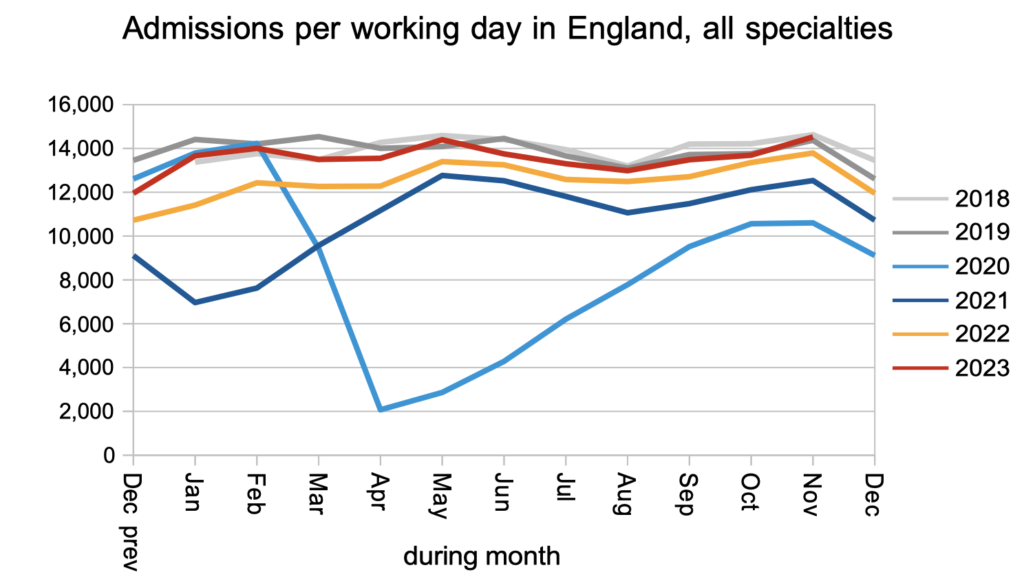

Patients were admitted from the waiting list, for treatment as inpatients and daycases, at slightly below pre-pandemic rates.

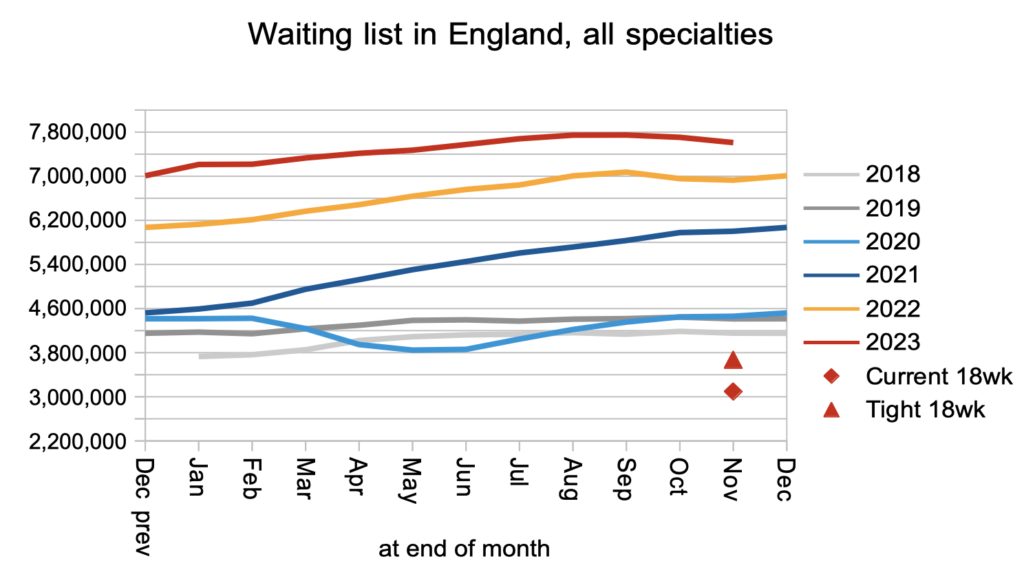

Overall, the RTT waiting list fell significantly which is very welcome. As the red triangle in the chart below shows, it needs to fall a lot further before the statutory 18 week target is likely to be achieved again.

Waiting times fell sharply on an RTT basis, and slightly for patients awaiting diagnosis and decision to admit. From a patient’s point of view it is the waiting time that matters, not how many other patients are also waiting.

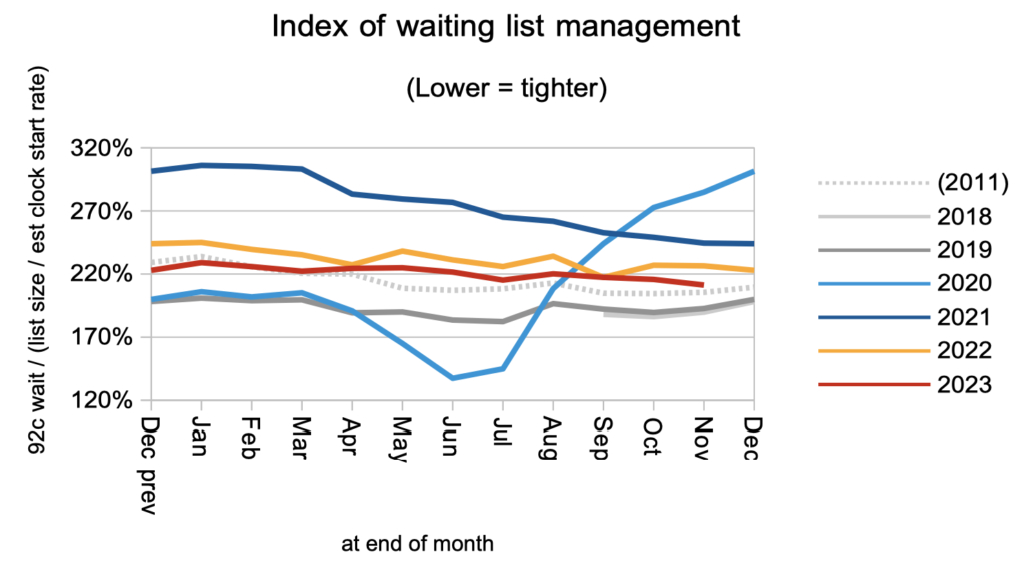

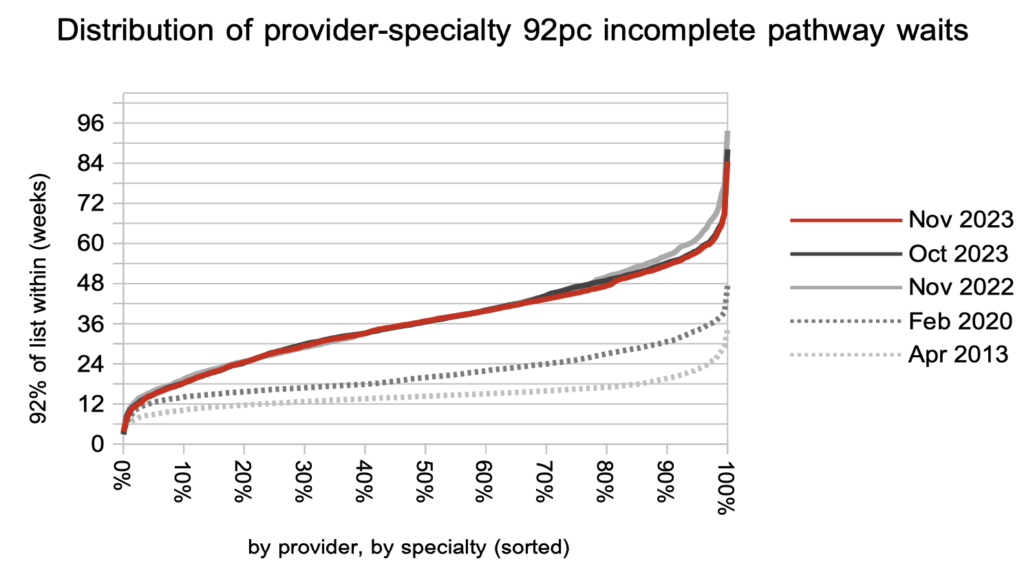

The shape of the waiting list improved slightly, but remains much worse than pre-pandemic.

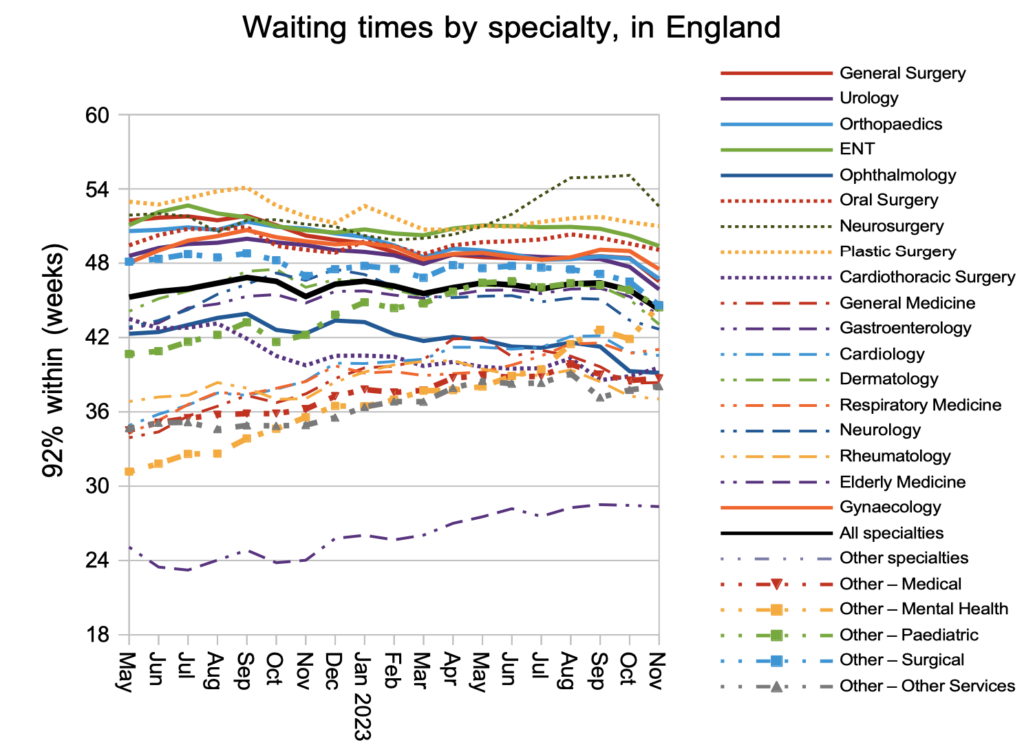

Breaking the national waiting times down by specialty, there was improvement in nearly all of them. The main exception is mental health waiting times which rose very sharply from 41.9 to 44.6 weeks RTT in a single month. It is difficult to know how much we can rely on the mental health RTT waiting times because not all mental health trusts submit data, but nevertheless this is a worrying development in this important sector of healthcare.

Looking at the distribution of waiting times in local specialties across England, the improvement in November was concentrated around the 52-week mark. This is consistent with the improvements over the last year which may be attributable to the targets to eliminate the longest waits.

Referral-to-treatment data up to the end of December is due out at 9:30am on Thursday 8th February.