Waiting time targets – like happiness – are best pursued indirectly

29/03/2016by Rob Findlay

Waiting times are a function of two things: the size of the waiting list (a long queue means long waits), and the order in which patients are scheduled (queue-jumping means the others wait longer). Queue-jumping is justified when patients are clinically urgent, so good patient scheduling means treating urgent patients quickly and safely, and routine patients broadly on a first-come-first-served basis.

So far, so uncontroversial. Or is it? Because the implication of this deceptively simple logic is that much of the NHS is going about its waiting list management the wrong way.

Take patient scheduling. Members of staff who book patients into clinic and theatre sessions (let’s call them schedulers) are commonly given a list of patients who are approaching the waiting time target, and asked to book them in before they breach it. But this bears only a slight resemblance to good scheduling, and (as we shall see) it causes a lot of problems.

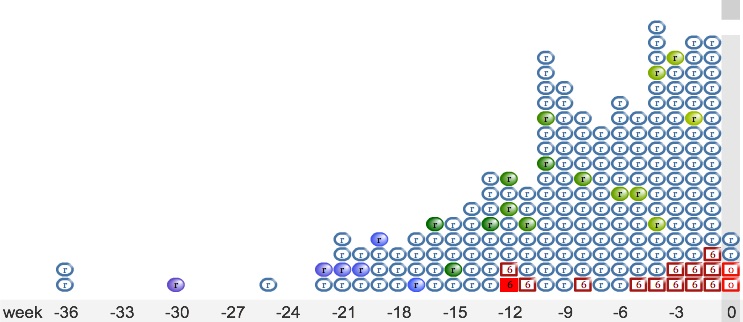

The problems begin with patients who are not the focus of attention – routine patients with short and middling waiting times. In most services, these patients are the majority. There isn’t any particular process for booking them, so they are booked out of turn, pushing up waiting times, filling capacity, and generally making it difficult for schedulers to find enough empty slots for the imminent long waiters. And this happens even if the waiting list is small. But with heroic effort the schedulers somehow get the imminent breaches booked in before they breach, and this feels like success.

What if the waiting list is too big? Now it is actually impossible to achieve the waiting times targets, but nobody tells the schedulers that. What they do know is that it is very difficult indeed to book all the imminent long waiters, but then life is always difficult so the difference is not clear cut. So they try harder, but fail. That is, I hope they fail, because the alternative is to succeed by delaying urgent patients which is unsafe. Or they might succeed by getting an extra session laid on at short notice (and high marginal cost) as a sort of micro waiting list initiative. Either way it feels like failure to them, even though the real problem – an oversized waiting list – was not their fault at all.

So this approach to waiting list management keeps waiting times close to the brink of failure, even if waiting lists are small. It lurches from unsafe to unfair – unfair to patients and unfair to the schedulers too. And the size of the waiting list is managed in a reactive and costly fashion that does nothing to address the underlying mismatch between capacity and demand.

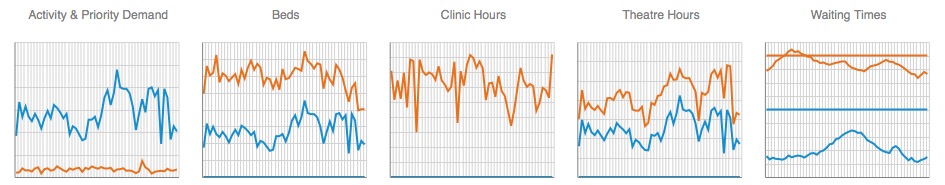

We can do better than this. Instead of managing long waiting times directly, let’s manage them indirectly by tackling their causes: the size of the waiting list and how patients are scheduled.

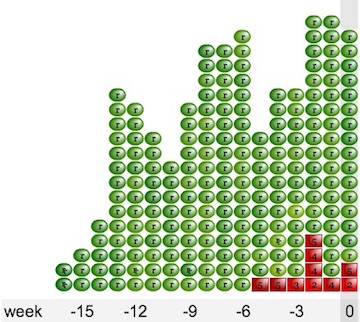

Scheduling first. We want to manage the whole system, instead of managing at the margins as before, so schedulers follow a set of rules that apply to every single waiting list patient. This means reserving the right amount of capacity for urgent patients who pop up at short notice, so they can always be booked within their safe time limits. Then routine patients get a choice of the next available routine slots, and they are booked broadly in date order. There are a couple of other rules that cover secondary situations, but that’s the guts of it, and with good and comprehensive booking rules it should be rare for problems to be escalated to managers.

What does this do to waiting times? That depends on the size of the waiting list. If the list is small then waiting times are short. If the waiting list is too big then waiting times will breach the target, as they should under the circumstances. Either way, the schedulers are doing a good job, and we know because the waiting list shape is nice and compact, and waiting times are consistent with our waiting time model when we tell it how big the waiting list is.

Which brings us to the size of the waiting list. Now that scheduling is consistently good, the only thing that determines waiting times is the size of the waiting list. This is the responsibility of managers, who need to plan the right amount of capacity through the year, so that the waiting list is always small enough to achieve the targets.

Now everybody knows their role. Schedulers schedule, and managers manage capacity. Nobody is judged for things that are not their fault. We have overturned the dictum that waiting times are everybody’s responsibility, and achieved something much better by separating responsibilities and specialising. Best of all, we are managing according to the needs of patients, and not to the target.

Return to Post Index

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.