Why 18 weeks might never be achieved again

31/05/2016by Rob Findlay

The NHS in England was expected to breach the 18 week waiting times target in March, but not by much (if at all). In fact, it breached by the biggest margin since the target was first introduced in 2012.

But this isn’t just a problem for March. This huge backlog is the starting point for every future waiting list – a waiting list that is already growing rapidly year-on-year.

The waiting list is now so large, it is quite possible that 18 weeks will never be achieved again.

The analysis

Last year I attempted to forecast when the 18 week target was likely to be breached for the first time. I reckoned that, if you added non-reporting Trusts back into the figures (as I have done throughout this analysis), this was most likely to happen at the end of December 2015. In fact it happened a bit earlier, in October. (Officially the first breach wasn’t until December, but that is based on figures that don’t allow for non-reporting Trusts.)

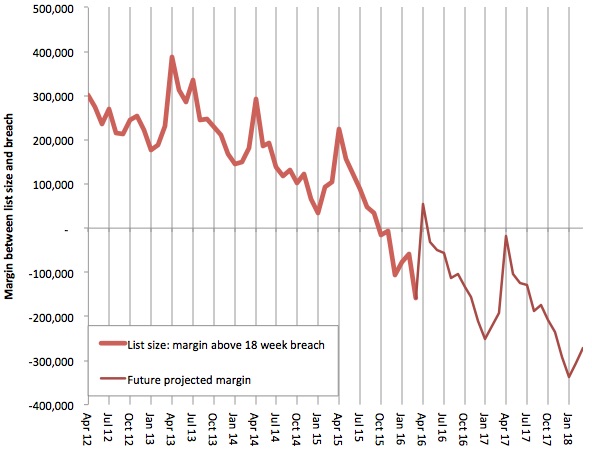

In the light of the latest dismal figures I have refreshed that analysis, and now it shows that 18 weeks might be achieved at the end of April by a small margin of 54,000 patients. When I originally ran the numbers last year the margin was a much larger 162,000, so you can see how quickly the position has deteriorated.

But that isn’t the end of the story. On 26th and 27th April the junior doctors held a strike, which according to NHS England caused 12,711 postponed elective operations (nearly all of which would presumably have resulted in clock stops) and 112,856 postponed outpatient appointments (of which I am guessing only a minority would have resulted in clock stops).

It is possible that those lost clock-stops could erase the margin of 54,000 patients and tip the English waiting list into breach at the end of April. Even if they don’t, then perhaps the disruption to patient scheduling will. Either way, the 18 week target looks fairly likely to have been breached at the end of April, and we will know for sure when the figures are published in early June.

After that things are expected to get steadily worse. The English waiting list is growing quite rapidly year-on-year, and this (not the junior doctors’ strikes) is the underlying cause of today’s 18 week breaches – a longer queue means longer waits. On top of that there are two seasonal effects: the waiting list grows in spring and shrinks in autumn; and patient scheduling is more disrupted during the winter months.

Those trends combine, so we typically get the shortest waiting times in April, followed by a steady decline towards winter, and then a rapid improvement towards the following April when waits are a bit longer because of the growing list. The following chart shows the current outlook:

When the line is above zero, it means that 18 weeks is achieved with a margin to spare. When it falls below zero, it means that 18 weeks is not achieved (adjusting for non-reporting Trusts) by the margin shown. You can see that in future there is only one month when the line is expected to rise above zero – April 2016 – but that does not take account of the junior doctors’ strike as discussed above.

A financial liability

Why have things deteriorated so much since my forecast last year? There are a few things I would pick out:

- Before Christmas, Monitor asked dozens of Trusts to reduce elective activity in order to create headroom on beds over Christmas and winter.

- The junior doctors’ strikes reduced capacity and increased disruption.

- King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust started reporting waiting list data again in March with a waiting list that was nearly 24,000 patients larger than previously reported.

But let us not allow these short-term effects to distract us from the underlying trend, which is that the NHS in England is not keeping up with demand, with the result that the waiting list is growing quite rapidly and so are waiting times.

The reasons are understandable in the present climate. Letting the waiting list grow requires less capacity and is cheaper. But bringing it back down again later is very expensive. You have to pay twice: once recurringly, to stop the growth from continuing; and then again non-recurringly, to clear the backlog that has accumulated.

It’s a bit like going steadily into debt. Except that waiting lists, unlike debts, do not appear anywhere in the NHS’s financial accounts. Perhaps they should? After all, every waiting list patient represents activity that has been ordered but not yet done or paid for.

If waiting lists were to appear in CCG financial accounts as a liability, even just in the footnotes, then it would be harder to pretend that the growing waiting list is a cheap option.

Return to Post Index

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.