Are the ’18 weeks’ trajectories deliverable?

12/08/2016by Rob Findlay

The “financial reset” document from NHS Improvement (NHSI) was mainly about money, but also about access. Some 12.5 per cent of the £1.8 billion Sustainability and Transformation Fund is conditional on Trusts achieving their 18 week waiting times trajectories, with the aim of bringing to an end the national breach of this statutory target.

Instead of continually penalising Trusts for breaches that they cannot immediately prevent, NHSI sensibly asked them to agree monthly trajectories for recovering the ’92 per cent within 18 weeks’ target. And expressing the trajectories as percentages helps to avoid the impression that the ’18 weeks’ bit has been relaxed (even if they can be as low as 72.16 per cent, as in the case of Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust).

What have Trusts signed up to?

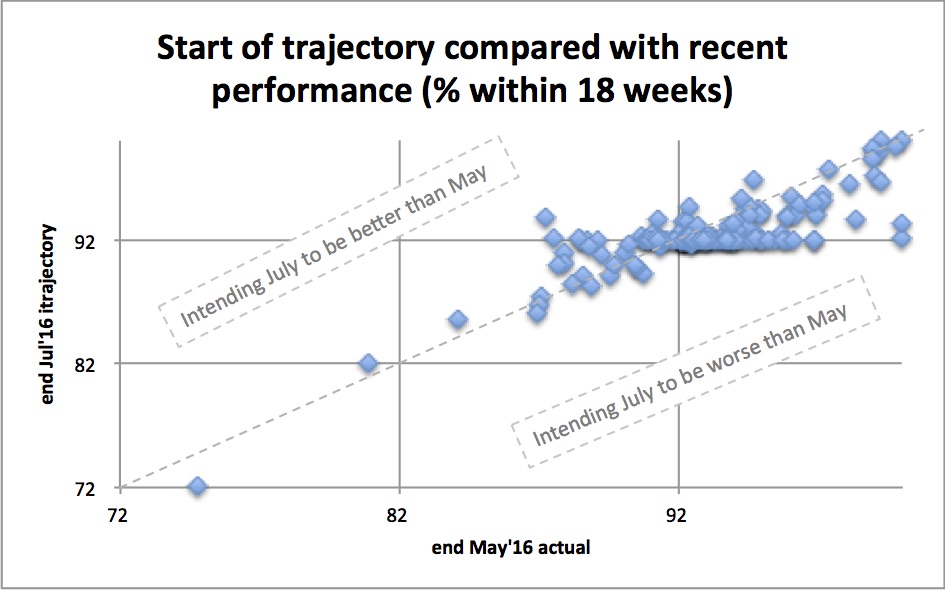

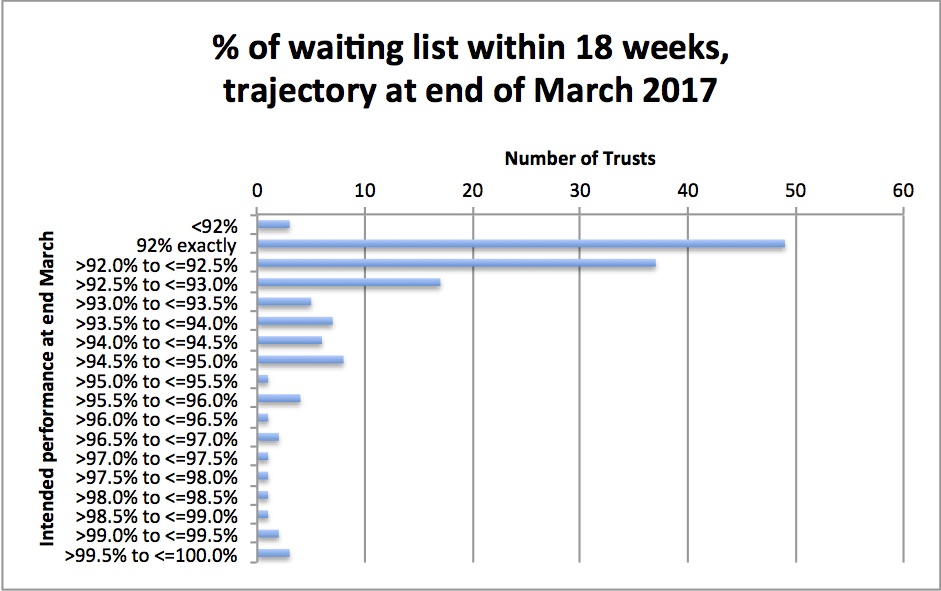

Trusts could have modelled their trajectories rigorously, taking account of things like winter emergencies and available capacity. But the spreadsheet models that most Trusts rely on would struggle with that. And it shows: more than one-third of Trusts’ trajectories simply keep between 92 and 92.1 per cent.

Most Trusts opted to begin their trajectories somewhere between 92 per cent and their actual performance at the end of May, which means a tough start for Trusts that are currently breaching, and a relaxed one for those who aren’t. And you won’t be surprised to hear that all trajectories end up achieving the 92 per cent target at the end of March, with only three exceptions for Trusts that are particularly challenged.

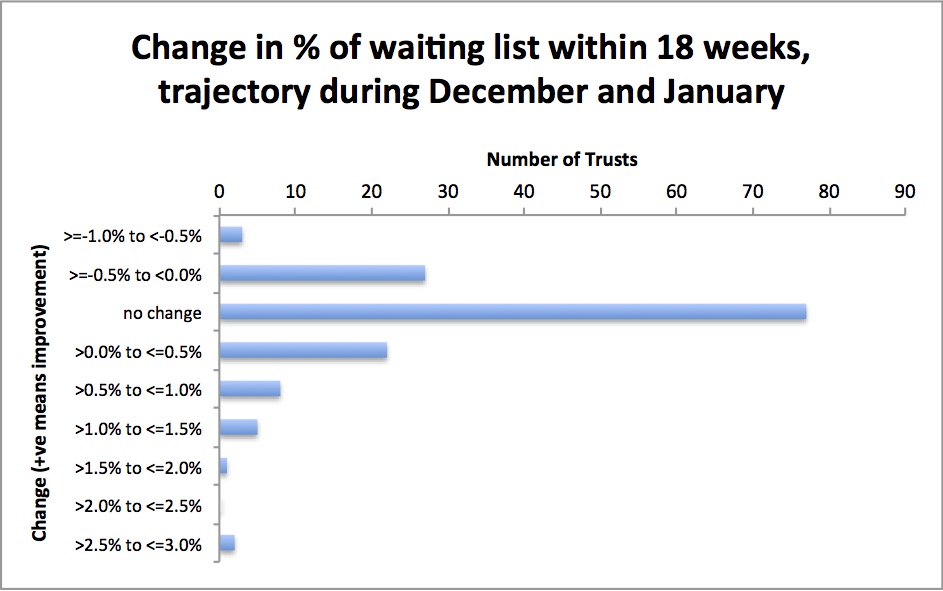

The surprises are in the middle, particularly in the months around Christmas when waiting times usually go up.

You might expect trajectories to anticipate things like the Christmas shutdown, patients’ reluctance to have surgery before Christmas, and winter bed pressures, by allowing waiting times to rise a bit in December and January.

In fact only 21 per cent of trajectories allow waiting times to rise in those months: 53 per cent keep waiting times constant (and half of those at exactly 92 per cent); and 26 per cent are planning to shorten waiting times in December and January.

The most dramatic example is Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, whose monthly trajectory shows a gradual deterioration from 86 per cent in July to 83.5 per cent at New Year, followed by a dramatic recovery to 87 per cent in January and finishing on target at 92 per cent at the end of March. The Trust’s Board minutes for July describe this as “realistic monthly targets for improvement by April 2017 taking into account seasonal pressures”. It is by a huge margin the most ambitious winter trajectory in the English NHS, and I wish them the best of luck.

Will it work?

These rosy trajectories are at odds with the national trends. Since 2012 the English waiting list has been growing rapidly – a sign that activity is falling chronically short of demand. A longer queue means longer waits, so waiting times have been rising and are now in persistent breach. I have previously forecast that unless something pretty big happens, the 18 week target will never be met again.

And yet the trajectories predict that 18 weeks will be met at the end of March. Who is right?

It all hinges on bringing activity and demand back into balance, and the “reset” document describes three ways of addressing this. The “immediate actions” include outsourcing to other providers, and containing referrals. And the “medium term actions” include “transforming elective services”.

Please excuse me for being underwhelmed.

Outsourcing is already happening, doesn’t save money, is oriented towards one-off initiatives, and usually cannot deal with the heavy casemixes which are often the main problem. So it is hard to see outsourcing initiatives closing this large recurring gap.

What about containing referrals? The amount of variation suggests that it’s possible. But CCGs have tried it, as did PCTs and Health Authorities before them, and the impact has always been limited. Referral thresholds can only be raised so far, and it’s often unpopular. After a scheme is abandoned, demand comes flooding back. How could this time be any different? Anything that really made a serious and sudden dent in elective demand would start a political firestorm.

What about transforming elective services? Actually this could make a difference. For instance, one-stop clinics can dramatically reduce the number of steps in a clinical pathway. And better use of operating theatres (which bizarrely were hardly mentioned in the 165-page Carter report) can reduce costs, smooth the demand for beds, and shorten waiting times. But this is serious work requiring careful study of demand and systems. Yes, it’s worthwhile. But it probably won’t close the yawning gap between activity and demand by March.

Time will tell. But if the 18 week target is restored across England by 31st March 2017 I will be very surprised. And if only three Trusts are breaching the target? As Alastair Campbell once promised – I’ll eat my kilt.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.